I discovered Whitney Stansell’s work in the most mundane of places – a conference room. While the conference room was in the aggressively hip SCAD-Atlanta complex, it was still a space of utility, not art. Her long canvas, Muscular Dystrophy Fair, simultaneously matched the functional aesthetic of the room and transcended it. An eight-foot horizontal canvas in washed out neutrals depicts a linear narrative of a small neighborhood block party, with notations describing the action – parents wait for children to put on a play while they sell tickets, a man charges admission to listen to his LP of Kennedy speeches, a girl gives an interview to a reporter. It is funny, nostalgic and beguiling. Postmodern in a way, but too sincere and warm to be pure irony

I contacted Whitney this summer, and found her to be friendly and genuine, reinforcing the sincerity of her work. I asked her to answer some questions about her process for my students and she gamely responded with insights about her sketchbooks, use of source images and interest in experimentation. She even sent along photos of her latest work. What follows below is the text of this interview. Please check out her work, at http://whitneystansell.com/

I contacted Whitney this summer, and found her to be friendly and genuine, reinforcing the sincerity of her work. I asked her to answer some questions about her process for my students and she gamely responded with insights about her sketchbooks, use of source images and interest in experimentation. She even sent along photos of her latest work. What follows below is the text of this interview. Please check out her work, at http://whitneystansell.com/Why do you paint?

I paint when I think it is the necessary medium in which I want to express my ideas. Sometimes I will draw with a marker, or draw by stitching with a black thread on a piece of raw canvas. I recently made a sculptural installation out of 1950’s women’s dress patterns. I think the medium can help to inform the message. Honestly, painting is a great deal of fun. All the possible colors one can make and the actual application are exciting to be apart of.

How do you know when a piece is working?

A piece is working when I am excited about it, when it is doing things for me visually as well as conceptually that I didn’t expect. I like for my work to surprise me. You can do a hundred thumbnails before beginning a piece, but you can’t figure everything out, and you shouldn’t. Sometimes you should trust yourself, and you ideas, and let it happen.

What do you do when it isn't?

Good question. Not often (I can think of three pieces out of about 35 in the past two years) that I just had to stop working on and start over. Honestly, if the piece is boring to me then I know I need to rework something about it.

Your work is fully realized thematically and visually. How do you develop concepts? How do you unlock the concept visually? Do you ever work in reverse (assigning meaning after completion)?

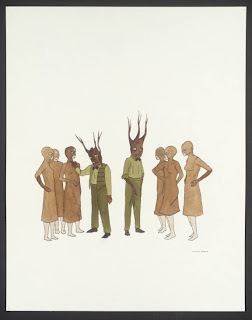

I think that some of the themes were discovered along the way….once you have a body of work that you are passionate about, the work just begins to build, and then suddenly you have a million possible directions to go in, and you should experiment and find what works best for you, and what you are trying to say. I spent time experimenting with the size and type of my text. (in a recent piece, that I will send you a jpg of) it took me a long time to figure out the size and placement of the text, (which I think was pivotal to the success of the piece) I really don’t think you have to have all the answers when you begin a work, just a few reasons for wanting to do it. Those reasons could be curiosity, a love for the subject, wonderment as to what happened to this or that person, or that event….. or what is going to happen if I do this…. I am not an abstract artist, but I have many friends who are, and there questions come from wondering what will the paint do if I do this? And that is interesting, and keeps them exploring.

To answer your question, how do I develop concepts? I work with things and ideas that mean something to me personally. That is most important to me. I simply then ask myself,,,,,, how can I make this into art.

Do you use source material?

Yes yes yes. I don’t see anything wrong with using source material. In fact, I think that artist imaginations work mimetically, I use my everyday surroundings in all of my work. So the Bakery in my paintings is the Bakery down the street. And the long row of houses in the Muscular Dystrophy Fair, are the houses behind my house. I also take a lot of pictures, and get different poses and body language from friends and family.

Do you let the work of others inspire you, or do you resist outside influence?

I do get inspiration from others. But I find that it is healthy to look at other types of artists, like filmmakers, or writers, or poets. That way you still have some work to do, and you don’t feel like you are simply re-doing something that has been done. It keeps it fresh. I look at a ton of art, because I love art. But I am not looking at art for it to necessarily inform my art.

What's in your sketchbook?

You know my husband, who is a filmmaker, gets onto me for not planning all of my compositions out in my sketchbooks. Like I said earlier, I take a lot of pictures, and spend a lot of time looking at them. I collage images to get a better sense of the way things could interact. So, my sketchbook is filled with lists. Lists of ideas. Lists of things I would like to do, and things I would like to try. I am also a big “imaginer” -meaning that I am always imagining a piece I want to work on. Most likely for two months I will imagine something before I ever begin even sketching. I do make thumbnails and sketches. They are usually very rough. I will only show my book to two people, it is that rough!

What advice would you give to your high school self?

Oh!! In high school I was in the art room A LOT. And I really enjoyed making work. I made A LOT of bad work. But, I just kept telling myself to work hard, and keep it up. Making is so much apart of who I am, that I really didn’t have a choice. J

So, my advice is, pursue your work with your whole heart. And work really really hard. And it is ok to make some cheesy stuff, and silly stuff. You should always be having fun. Its funny, you don’t want to take yourself to seriously, but then, you really want to believe in yourself, and take yourself so seriously. High school, is the time to have fun! And experiment.